Children influence spending within their households. Viacom conducted a national study in 2017 which found that three out of four parents said their children influenced their purchase decisions. Among these decisions is whether to buy a particular toy. The toy market is expanding with the pandemic: a NPD report found it to be worth 251 billion in 2020, up 19% from 2019, as parents wish to keep their children entertained (especially during work-related Zoom calls…) In France, the toy market is the fifth biggest one in the world.

Toy manufacturers have found in the last few years a novel way to promote their goods. “Influencer children” are filmed, often by their own parents, opening boxes of products sent by companies hoping to be featured in the videos, or which have entered a contract for the products to be featured. The videos are then uploaded on video-sharing platforms. Some YouTube channels featuring children influencers boast millions of views. Some of these channels generate advertising revenues in the millions of dollars.

In France, the Studio Bubble Tea channel is the project of a father featuring his two daughters, Kalys and Athéna, and has some 1.7 million subscribers. The videos show the two young girls opening packages (unboxing videos), sampling fast food or sugary treats, and now even presenting derivative products featuring their likenesses, as they have become famous on their own. Another team of siblings, two boys, Néo and Swan, are starring in the YouTube The Voice – Neo & Swan channel, which has more than 5.3 million followers, also opening huge boxes of toys and other merchandise, visiting themes parks, doing challenges, such as the “Gummy Food v. Real Food Challenge.”

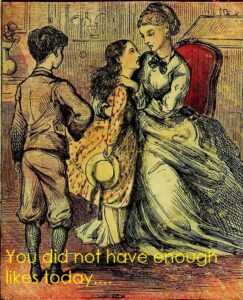

Is this work, or just kids having fun?

The frequency of posting of these videos, several times a week, and their nature, often a scripted, or semi-scripted scenario, playing for a half-hour or more, made the French legislators wonder: was it work or play?

Before the introduction of the bill, French Representative Patrick Mignola had asked in June 2018 a written question to the Secretary of Labor to alert her about the absence of any regulation of the online work of these minors, stating that these activities should be considered work by the French labor Code, and asking the position of the government on the issue. The Secretary answered that she believed that such activities were considered by the law to be leisure, not work. She stated, however, that:

“[t]his phenomenon, both in terms of volume and of financial flows, now leads to questions about the qualification of “leisure activities” with regard to criteria, notably identified by case law, which characterize the employment relationship such as the obligation to take part in the activity, to follow unilaterally defined rules, guidance in the analysis of conduct or permanent availability, the possibility of sanctioning any breach of these obligations. All videos uploaded do not meet these criteria.”

The Secretary of Labor noted further that “ the “superposition” between the bond of subordination and parental authority must not serve to mask a possible work performance,” and agreed that the legal framework of this activity needed to be clarified.

French law considers three cumulative factors to assess the existence of a working relationship: work performance, remuneration and relationship of subordination. The latter factor is most of the time lacking when assessing the activity of “kidfluencers,” as most of them perform at the direction of their parents. A report on a bill aiming at regulating the work of children influencers, authored by Representative Bruno Studer, published on February 5, 2020 (Studer Report), noted that:

“many situations do not meet the combination of these three conditions. For example, the child filmed in the course of his or her daily life does not provide any service; some videos are not monetized; the child does not necessarily receive instructions or orders from the director-producer of the video. Thus, for the children concerned, the working time, the income generated, the morality of the content or even the respect of school obligations, dodge any legal framework.”

The Parliament passed the bill unanimously, which was then sent to the Senate. Senator Jean-Raymond Hugonet wrote in his report (the Hugonet report) that, “[w]hile some of these videos are clearly degrading, the majority of them are heartbreaking, even pathetic. They present children in different activities – unwrapping toys, scenes from everyday life, various challenges such as spending 24 hours in a closet or eating food of a certain color for 24 hours.”

The bill became law on October 19, 2020, regulating the commercial exploitation on platforms of children younger than 16 years old (Loi n° 2020-1266 du 19 octobre 2020 visant à encadrer l’exploitation commerciale de l’image d’enfants de moins de seize ans sur les plateformes en ligne) (the influencer law). The law will be implemented six months after its publication, was was on October 19, 2020.

The Studer Report mentioned the “sadly infamous cheese challenge,” also mentioned in the Hugonet report, where people produced videos showing them throwing slices of cheese in babies’ faces, as one of the reasons for passing the law. Such videos are not, however, posted on video channels dedicated to one or more child presenting products and services.

The Studer report painted a particularly dark picture of the use of children as influencers as it also mentioned a U.S. case where a mother who was featuring her children on her YouTube channel was charged with child abuse as the children were allegedly abused, including being undernourished and pepper sprayed for punishment. A third-party web site estimated the mother’s earnings from the channel at a minimum of six, maybe seven figures. However, these examples are thankfully the exception, not the rule, and the influencer law is not a child welfare protection law, even though the issue of whether child influencers may suffer ill psychological effects because of their media exposure was alluded to during the debates at the Parliament.

French child labor law and minors under 16

The new law modifies the labor Code to liken “kidfluencers” to children working in the entertainment industries or as fashion models so they too can benefit from ad hoc legal protection.

Under French labor law, minors aged sixteen at least may work, but children less than sixteen years old cannot. Article L7124-1 of the French Labor Code carves out, however, exceptions for children engaged in entertainment activities, working on films, radio, or television programs, working as a fashion model, or, since the October 7, 2016 “law for a digital Republic,” children participating in video game competitions. In these cases, the law requires obtaining a prior individual administrative working authorization.

Article L7124-9 of the French labor Code authorizes part of the minor’s earnings to be made available to the child’s legal representatives. However, “[t]he surplus, which constitutes the nest egg, is paid to the Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations and managed by this fund until the child reaches the age of majority. Direct debits may be authorized in emergency and exceptional cases.

Article L7124-25 of the French labor Code punishes by a 3,750 Euro fine the giving ”directly or indirectly,” to the minor or their legal representatives, the funds which should have been placed in the child’s nest egg account.

What the influencer law changed

The influencer law broadened the scope of article L7124-1 to include children working for an employer “whose activity consists in making audiovisual recordings of which the main subject is a child under the age of sixteen, with a view to distribution for profit on a video-sharing platform service.” As worded, the law protects children performing on influencer videos, even if they do not have a work contract, which is most often the case, as the videos are often produced by the child’s own parents.

The law broadened the scope of the special legal status of children performers under sixteen under article L7124-1 2°) to participation in “sound recordings or audiovisual recordings, whatever their modes of communication to the public.” The law also created article L7124-1 5°, which places under the scope of the special status children working for an employer “whose activity consists in making audiovisual recordings of which the main subject is a child under the age of sixteen, with a view to distribution for profit on a video-sharing platform service,” thus alluding specifically to video posted on platforms.

The mandatory work authorization – Article 3- I

An authorization to feature a child below sixteen in a video shared online, if the child is “the main subject” of the video, must be obtained by the child’s legal representatives in the following cases:

- When the cumulative duration or the number of these contents exceeds, over a given period of time, a threshold fixed by decree of the Council of State [this threshold has not yet been determined] or;

- When the distribution of these contents provides an income to the director, producer or distributor of the video, whether this income is direct or indirect income, superior to a threshold fixed by decree of the Council of State [this threshold has not yet been determined].

These two cases are not cumulative. The Hugonet report noted that “the two conditions, even though close, do not necessarily merge. Parents may well choose not to monetize a video that “goes viral,” which does not rule out damage to the exposed minor. Likewise, some video content can generate income without necessarily having a large audience, through product placement, if the people filmed are deemed to be “influencers.”

The administrative authority makes recommendations to the legal representatives about:

- The times, duration, hygiene and safety of the conditions for making the videos;

- The risks, in particular psychological, associated with the dissemination of these videos;

- The legal requirements about allowing normal school attendance;

- The representative’s financial obligations incumbent on them .

The administrative authorization necessary to have children under sixteen perform in such videos is provided temporarily but can be renewed. The authorization can, however, be revoked at any time, and, in case of urgency, can even be suspended for a limited time. The influencer law does not define nor explain what these urgent matters are. While waiting for the decision to be issued, the authorization may be suspended.

Article 5 of the law added article 6-2 to the June 21, 2004 law on confidence in the digital economy, the French law regulating platforms and web-based activities, which provides that, if the administrative authority in charge of delivering the authorization finds out that a video featuring minors under sixteen has been posted on a platform without prior authorization, the administrative authority may refer the matter to a judge who can then “order any measure to prevent imminent damage or to put an end to a clearly unlawful disorder.” The use of the term “imminent” indicates that the procedure to be issued is the emergency procédure de référé, allowing the judge to issue a ruling rapidly, even within two days if following the exceptional procedure of référé d’heures à heures. The Hugonet report approved the introduction into the bill of the intervention of the judge as it “constitutes a strong guarantee… to respect the principle of freedom of expression.”

Article L7124-1 of the Code will require, when the influencer law enters into force, that, once the authorization to have a child perform in the video is obtained, the administrative authority must provide the child’s legal representatives “information relating to the protection of the rights of the child in the context of the production of these videos, which in particular covers on the consequences, on the child’s private life, of the dissemination of his image on a video-sharing platform.” The representatives must also be informed of financial obligations incumbent on them.

The financial obligations of the legal representatives & the marketing companies – Article 3-III & 3- IV

The Studer Report noted that it is the parents of a child performing in an influencer video who directly receive the revenue, and the child does not benefit from the protection of the French Labor Code provided to children performers. The salaries of children performers must be paid, until they turn eighteen, to a special escrow account at the Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations, which is a public financial institution.

Article 3 of the influencer law states that if the direct and indirect income derived from the distribution of the videos exceed, over a given period of time, a threshold set by decree in the Council of State, the income received from the date on which this threshold is exceeded must be paid without delay by the marketing company to the Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations which will then manage the income until the majority or emancipation of the child. A portion of the income, determined by the competent authority, can be left at the disposal of the child’s legal representatives.

A right to be forgotten – Article 6

The influencer law also addressed the issue of privacy. Its article 4-6° directs video-sharing platforms to adopt charters codes aiming at facilitating a minor’s right to be forgotten, which is provided to them by article 51 of the French data privacy law. These charters must inform the children using “clear and precise, easily understandable terms,” how this right can be implemented.

Article 6 of the influencer law specifies that parental authorization is not necessary for the child to exercise this right. Article 7 of the law directs the government to provide the Parliament, within six months of the publication of the law, that is, April 19, 2021, at the latest, a report evaluating the reinforcing of the protection of the personal data of minors since the implementation in France of the GDPR.

As explained by the Studer report, a minors’ right to be forgotten belongs to the holder of parental authority. However, in the case of a child influencer, “there are many situations in which parents are responsible for distributing content showing their children and find it beneficial, particularly from a financial point of view, to keep this content online.”

The new duties of the marketing companies under the new law – Article 3-IV – how to pay the child

Article 3-IV of the law provides that advertisers placing a product “in an audiovisual program broadcast on a video-sharing platform whose main subject is a child under the age of sixteen” must verify with the person responsible for the broadcast if the monies due for the product placement must be paid to the Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations. If this is the case, the marketing company must pay the child salary directly to the Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations, minus the part of the salary which may be kept by the legal representatives under the law. Failure to comply with the obligation to pay to the Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations is punished by a 3,750 Euro fine.

The new duties of the marketing companies under the new law – Article 4 – adopting charters

Article 4 of the law gives marketing companies the duty to adopt charters which must aim inter alia:

- To promote information to users on the laws and regulations applicable to the dissemination of the image of children under sixteen through video-sharing services and on the risks, particularly the psychological risks, associated with the dissemination of these images;

- To promote information and awareness of minors less then sixteen years old, with the help of non-profit child protection organizations, about the consequences of the dissemination of their image on a video-sharing platform of their private lives, the psychological and legal risks of such use and the recourses they may use “to protect their rights, dignity and moral and physical integrity;

- To promote users reporting of content featuring children under the age of sixteen which would infringe upon the dignity, moral or physical integrity, of these children;

- To take “all useful measures to prevent processing, for commercial purposes, such as commercial solicitation, profiling, and behavioral advertising, of the personal data of minors that would be collected by their services through the posting by a user of audiovisual content in which a minor appears;”

- “To improve, in connection with child protection nonprofit organizations, the detection of situations in which the production or distribution of such content would violate the dignity or the moral or physical integrity of minors under the age of sixteen years that they include;”

- To facilitate the minors’ implementation of their right to be forgotten, as provided to them by article 51 of the French data processing law, the law n ° 78-17 of January 6, 1978. Such information must be provided “in clear and precise terms, easily understandable by [the minors] of the methods of implementing this right.”

Article 5 of the law states that the French communications agency, the Conseil supérieur de l’audiovisuel (CSA), the French public authority for audiovisual regulation, “will publish periodic reports on the implementation and effectiveness of these charters.” The Hugonet report noted that “[t]his “soft law” approach is in fact the only alternative, in an online world where more direct regulation is legally impossible, not to mention the possible infringements of freedom of expression.” It is not clear whether the charters will be public or internal best practice documents. The CSA reports should, however, be made public and thus provide practitioners with useful information.