The US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit issued last month an important decision for artists. The Andy Warhol Foundation, which had filed a brief of amicus curiae in favor of Prince, stated that it “does not object to other artists building freely on Mr. Warhol’s work in the creation of new art, because it recognizes that such freedom is essential to fulfilling copyright’s goal of promoting creativity and artistic expression.“

The US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit issued last month an important decision for artists. The Andy Warhol Foundation, which had filed a brief of amicus curiae in favor of Prince, stated that it “does not object to other artists building freely on Mr. Warhol’s work in the creation of new art, because it recognizes that such freedom is essential to fulfilling copyright’s goal of promoting creativity and artistic expression.“

At issue was whether Richard Prince’s artwork had made fair use of Patrick Cariou’s copyrighted photographs.

Patrick Cariou published in 2000 a book, Yes Rasta, which featured photographs taken during his 6-year long stay in Jamaica. Richard Prince used some of these photographs to create his Canal Zone series. Prince enlarged the Cariou photographs and sometimes cropped them. He also painted over on some of the faces and bodies of the subjects of the photographs, but used some of the Cariou photographs almost entirely. Prince did not seek licensing nor did he ask Cariou for permission to use his work.

Canal Zone was exhibited at the Gagosian Gallery in New York, and the gallery also published and sold a catalog for this exhibition reproducing the Richard Prince’s artworks.

Cariou sued both Prince and the Gagosian Gallery for copyright infringement, and the defendants raised a fair use defense. Fair use is an affirmative defense to a claim of copyright infringement. The United States District Court for the Southern District of New York (SDNY) found in 2011 that the use by Richard Price of photographs taken by Cariou to create his Canal Zone series was not fair use. It consequently ordered all infringing copies of the series to be delivered so that they can be destroyed. Defendants appealed.

The Second Circuit held on April 25 that the SDNY had applied the incorrect standard to determine whether Prince’s use of Cariou’s work was fair use, and concluded, after extensive analysis of the paintings, that all but five of Prince’s works made fair use of the original works. The Court remanded to the SDNY to decide whether Prince is entitled to a fair use defense for these five works as well.

What is Appropriation Art?

As noted by the Second Circuit, “Prince is a well-known appropriation artist” and quotes a definition of the Tate Gallery of appropriation art as “the more or less direct taking over of work of art a real object or even an existing work of art.”

The Gagosian Gallery describes Prince’s way to work as “[m]ining images from mass media, advertising and entertainment” adding that “Prince has redefined the concepts of authorship, ownership, and aura.”

Another artist using such techniques, Jeff Koons, was also the defendant in several fair use cases. In Blanch v. Koons, the Second Circuit held in 2006 that the use by Jeff Koons of a copyrighted fashion photograph in his collage painting, Niagara, was fair use.

Fair Use Defense

As noted by the Second Circuit in its Blanch v. Koons decision, referring to such art as ‘appropriation art’ may be unfortunate in a legal context. Indeed, copyright law provides copyright owners exclusive rights in their works, and appropriation of a copyrighted photograph to create a new work may or may not be fair use. In practice, it means that the outcome of a fair use case is difficult, if not impossible to predict.

So, what is fair use? The Copyright Act, 17 U.S.C. § 107, provides a fair use limitation on copyright owners ‘rights, and provides four non-exclusive factors that courts must follow in order to find out, case by case, if a particular use of a protected work is fair. These four factors are:

1) The purpose and character of the use (the transformative use, the commercial use)

2) The nature of the copyrighted work

3) The amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted works as a whole

4) The effect of that use on the market

The SDNY had found that none of these four factors supported a finding of fair use in favor of the defendants.

I will discuss the fair use factors in the order used by the Second Circuit.

First Factor: What is Transformative Use?

The Supreme Court explained in the 1994 Campbell v. Acuff-Rose case what constitutes transformative use. The new work adds something new, and alters the original work while adding a new expression or message. Even if it is not necessary that the use be transformative to find fair use, the Supreme Court noted that “[s]uch transformative works lie at the heart of the fair use doctrine.”

The SDNY interpreted transformative use as meaning that the new work has to comment on the original work, and that if Prince’s works would “merely recast, transform, or adapt the [Cariou] [p]hotos,” they would be infringing. Prince had testified that he did not intend to comment on the original work of Cariou, nor even on “the broader culture,” and thus the SDNY concluded that the first factor weighted against the Defendants.

However, the Second Circuit found that, because the new work does not necessarily have to comment on the original work in order to be transformative, the SDNY had applied an incorrect legal standard. Instead, the Second Circuit stated, quoting Campbell, that the “new work generally must alter the original with “new expression, meaning or message.””

The Second Circuit found than most of the Prince works added something new to the plaintiff’s photographs and “presented images with a fundamentally different aesthetic.”

First Factor: The Commercial Use

The SDNY also found that the Defendant’s use of the Carious’s photos was “substantially commercial” as Gagosian sold paintings from the Canal Zone series for a total of $ 10,480,000.00, traded some for other works of art at an estimated value of $6 million to $8 million, and also sold catalogs of the exhibition. However, the Second Circuit, while noting that Prince’s works are indeed commercial, did not give much significance to it, as his work was transformative enough to make the issue of commercial use insignificant.

Fourth Factor: The Effect on the Market

As Prince’s work is highly transformative, it did not usurp the primary or derivative market for Cariou’s work. The record shows that Cariou had not marketed his work “aggressively.” He earned about $8,000 in royalties from the sale of his Yes Rasta book, and only sold four prints of the photographs. Also, the potential buyers of Prince’s works are not the same than Cariou’s works. The Second Circuit noted for instance that Jay-Z and Angelina Jolie were invited to the opening diner of the Canal Zone show at Gagosian.

Second Factor: The Nature of the Work

The defendants had unsuccessfully argued in front of the SDNY that Cariou’s works were merely compilations of facts about Jamaican Rastafarians, and thus not protected by copyright. The Second Circuit pointed out that it is undisputed that Cariou’s work is creative. However, as Prince’s work used it for transformative purpose, this factor has limited, if any use.

Third Factor: The Amount of the Use

While some of the original photographs of the Yes Rasta book can easily be recognized in the Canal Zone series, others are hardly identifiable as in, for instance, James Brown Disco Ball (you can see it here). However, the photograph taken by Cariou of a man looking at the camera from a three quarter angle is easily recognizable in Graduation, in spite of the addition of a guitar and the paint over the face.

Even copying the entirety of a work may be fair use. The SDNY found that Prince had taken more of the Cariou work than necessary, but the Second Circuit points out it is not required by law to only take what is necessary, and, in any case, it could not understand how the SDNY had actually come to that conclusion.

The Second Circuit engaged in its own pictorial analysis, and came to the conclusion that twenty five of Prince’s photographs transformed Cariou’s work “into something new and different,” but that Graduation, Meditation, Canal Zone (2008), Canal Zone (2007) and Charlie Company were not transformative enough, and remanded to the SDNY to determine if these five works are indeed transformative.

Judges as Art Experts?

Senior Circuit Judge Wallace, from the Ninth Circuit, sitting by designation, concurred with the majority that the SDNY had applied an incorrect legal standard. However, he dissented in part as, he believed that the whole case should have been remanded to the SDNY so that the lower court could analyze all the paintings using the proper standard, after new evidence is presented. Judge Wallace regretted that the Second Circuit judges used their own artistic judgment to determine whether the works were transformative or not. Fair use is a mixed question of law and fact. Therefore, each fair use case requires extensive analysis of the works of both plaintiff and defendant, even to the point as making a judgment of the worthiness of a particular work. This is troubling, and Justice Holmes famously wrote in the 1903 case Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographing Co. that “[i]t would be a dangerous undertaking for persons trained only to the law to constitute themselves final judges of the worth of pictorial illustrations.”

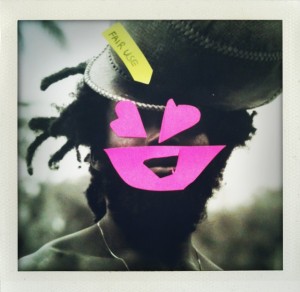

The image is my own play with a photography from the Yes Rasta book… Yes, it was a wise choice to go to law school, not art school…